The bird that was turned into a study mount was December Crow -- after I had finished photographing the body, I turned it over to the bird division, so that it could be added to the collection (a few months prior, I had donated October Junco, as well). What transpired on Friday afternoon was fascinating; in three hours, the crow turned from looking like a crow to not looking at all like a crow -- and back again. While my photographic subjects usually decay and break down, returning to the environment, this one was preserved, and will live on in a different way.

Naturally, I brought my camera and documented a good portion of the process -- the skinning, bone-sawing, muscle-removing, stuffing, and pinning -- the whole lot. Some of the photographs that follow might be considered disturbing (though in my mind, they are no more graphic than walking down the meat aisle at the grocery store, or, for that matter, any more graphic than the photos I've posted of animals decaying in nature).

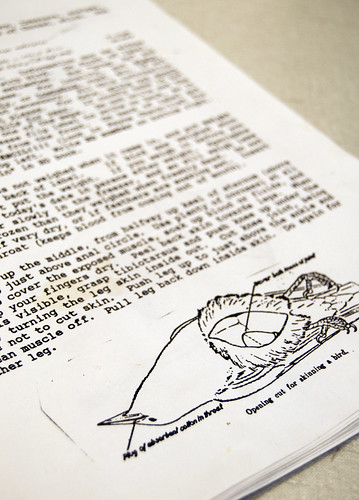

When I arrived, December Crow had already been thawed. The body sat breast-up on a long table, atop a few pages of newspaper. Nearby were scalpels and scissors, a pin cushion and thread, a roll of cotton, and a yogurt cup containing corn meal. Mary Margaret started by finding the crow's breastbone beneath all those black feathers, and separated the down on either side of the keel. I soon learned that birds aren't covered in feathers, rather, they grow along feather tracts, and there's a good deal of skin where the feathers don't actually attach.

Mary Margaret made an incision down the keel of the breastbone, all the way to the base of the tail. The crow's skin was paper-thin, and looked ever so delicate. As she pulled the skin away from the body, I marveled at how it didn't tear. At this point, the corn meal came into play: it is used to absorb any liquid or blood that might be present. When she reached the crow's legs, I was amazed at how large and red the muscles were. Since most of the legs stay with the skin, Mary Margaret cut through the thighs -- muscles, bones, and all. It wasn't a pleasant sound. She removed as much of the muscles and ligaments as she could; once the legs had been cut from the body, the crow's talons flopped on either side of the skin, looking quite unnatural and useless.

Mary Margaret made an incision down the keel of the breastbone, all the way to the base of the tail. The crow's skin was paper-thin, and looked ever so delicate. As she pulled the skin away from the body, I marveled at how it didn't tear. At this point, the corn meal came into play: it is used to absorb any liquid or blood that might be present. When she reached the crow's legs, I was amazed at how large and red the muscles were. Since most of the legs stay with the skin, Mary Margaret cut through the thighs -- muscles, bones, and all. It wasn't a pleasant sound. She removed as much of the muscles and ligaments as she could; once the legs had been cut from the body, the crow's talons flopped on either side of the skin, looking quite unnatural and useless.

After plugging the crow's mouth with cotton, the next step was to sever the vertebrae at the base of the tail; it was another unpleasant sound. As the skin was pulled back further, the wing bones were the next to be cut. Soon, all that was left connected to the skin was the neck and head of the crow. Though the crow's pectoral muscles were quite impressive, its skinned, little body looked awfully pathetic.

Mary Margaret continued to pull the skin back along the crow's neck, until she reached the skull. Soon, we could see the eyelids -- that is, the other side of them. Set inside the large eye sockets of the skull, the crow's eyes were bulbous and blueish, and with a pair of forceps, Mary Margaret carefully removed them. It was probably the most revolting step of the process; surprisingly intact after removal, they looked like large, overripe blueberries. At some point, the tongue was cut from the mouth, and I was surprised to see that the tip was forked.

In order to maintain a sense of shape in the bird's head, most of the skull is left inside the study mount. With a pair of surgical scissors, Mary Margaret cut out the very back of the skull, carefully tugged on the body, and out came the brain. It was rather large, but seeing as how crows are intelligent creatures, I wasn't too surprised!

At this point, several things were done, and I can't quite remember the order in which they were completed. The cotton was removed from the crow's mouth, meat was trimmed from the wings, and fat was scraped away from the inside of the skin. After packing cotton into the empty eye sockets, Mary Margaret slowly pulled the skin back over the skull. Finally, December Crow was starting to look like a crow again.

To keep the wings in place, a thread was looped through the radii. Cotton was then wrapped around a wooden dowel and was shaped to mimic the body cavity of the crow; it was inserted into the skin, the sharpened point connecting with the skull.

Soon, the crow was sewn back together. Despite all that muscle-cutting and turning inside-out, the incision in the skin really wasn't that big. After it had been stitched shut and the feathers smoothed back into place, I couldn't tell that the crow had ever been cut open. The study mount was pinned into a perfect position for drying: belly-up, wings tucked against the body, tail feathers slightly spread. The beak was tied shut, as when birds dry, their beaks tend to open.

Pinned to dry, December Crow looked decidedly different than it had when I'd photographed it on Christmas day. The crow seemed far more dead: a shell of what it had been, positioned neatly against a cork board, held down with pins.

Pinned to dry, December Crow looked decidedly different than it had when I'd photographed it on Christmas day. The crow seemed far more dead: a shell of what it had been, positioned neatly against a cork board, held down with pins.

I learned several things that afternoon, as I'd hoped. For one, December Crow was male. He was young, too, as the inside of his mouth was pale instead of black, as it is with adult crows. He was also quite healthy when he died: there was no sign of trauma anywhere on the body, and he was at a very healthy weight. Had he died in the summer, it would likely have been due to the West Nile virus, but his wintertime death is a little more mysterious.

The process of making a study mount also had its surprises: there was almost no blood to be seen, and, most surprising of all, there were no chemicals used to preserve the skin. Because almost all the flesh was removed, and because bird skins are so thin, they dry quickly and chemicals are simply not necessary.

In all, the experience (which took nearly three hours) was both interesting and educational. Though I would rather see animals decay in nature and be used entirely by the environment, I can understand and appreciate the worth behind preserving specimens for science.

The process of making a study mount also had its surprises: there was almost no blood to be seen, and, most surprising of all, there were no chemicals used to preserve the skin. Because almost all the flesh was removed, and because bird skins are so thin, they dry quickly and chemicals are simply not necessary.

In all, the experience (which took nearly three hours) was both interesting and educational. Though I would rather see animals decay in nature and be used entirely by the environment, I can understand and appreciate the worth behind preserving specimens for science.

No comments:

Post a Comment