In June, an individual donated his collection of big game trophy mounts -- that is, the heads and horns of a couple dozen African animals, including many antelopes and even a rhinoceros -- to the Mammal Division. They were all quite impressive to see firsthand, and though the horns were magnificent and all, what really struck me were the faces of these animals. Even though they were all long dead, they looked so alive and calm, and in their state of stillness, were incredibly emotive.

Another interesting thing about taxidermy is how incredibly awkward it has the potential to be. If the mount is not positioned correctly -- say, instead of hanging on a wall, an animal's head is against a horizontal surface -- the whole effect is thrown off, and it makes for a very surreal scene.

(The antelopes and hartebeest hanging on the wall behind the giant eland have been at the museum for some time.)

Of course, we photographed other specimens, too. There are a handful of older taxidermy mounts on display, and although some of them aren't in very good condition, they are important because they are the Mammal Division's only examples of those particular animals.

Of course, we photographed other specimens, too. There are a handful of older taxidermy mounts on display, and although some of them aren't in very good condition, they are important because they are the Mammal Division's only examples of those particular animals.

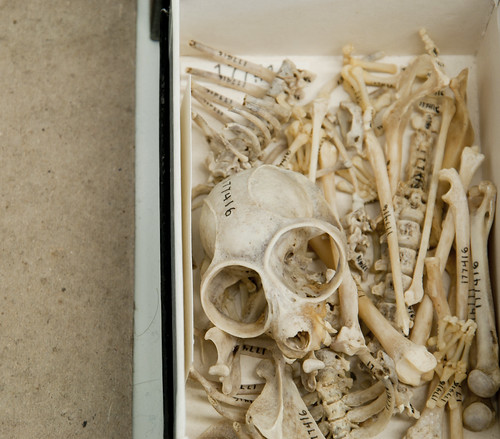

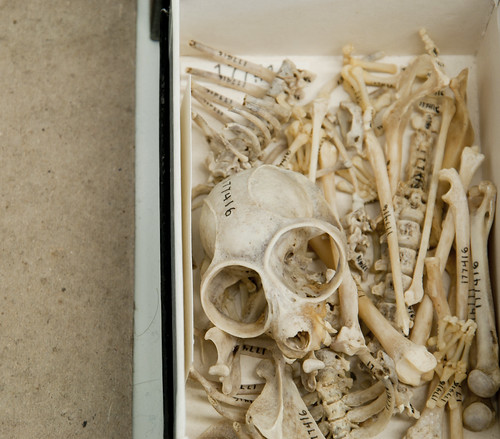

Stored in the cabinets are the skeletons, furs, and study mounts of almost every species of mammal imaginable. We perused several drawers' worth of coyote skulls and bones; a different cabinet was full of raccoons and mustelids.

Though these animals aren't what most would consider "useless creatures", I do feel they relate to my project. Big game trophies and museum mounts are respected and accepted more readily than the decomposing raccoon in the woods; they are useful in that they have scientific value; they are majestic because, in the case of the African trophies, they were hunted and killed by a human. Because people have a hand in their fate -- and because their deaths and subsequent preservation are useful to us -- these animals are perceived quite differently than their ecosystem-feeding kin.

I find taxidermy to be of equal value to the decaying animals in the wild. While museum taxidermy helps us learn and study the natural world around us, the dead animals in the forest and along the beach help feed the world that we study.

Though these animals aren't what most would consider "useless creatures", I do feel they relate to my project. Big game trophies and museum mounts are respected and accepted more readily than the decomposing raccoon in the woods; they are useful in that they have scientific value; they are majestic because, in the case of the African trophies, they were hunted and killed by a human. Because people have a hand in their fate -- and because their deaths and subsequent preservation are useful to us -- these animals are perceived quite differently than their ecosystem-feeding kin.

I find taxidermy to be of equal value to the decaying animals in the wild. While museum taxidermy helps us learn and study the natural world around us, the dead animals in the forest and along the beach help feed the world that we study.